OP-ED

Drugs markets in the islands of the western Indian Ocean (Part Two) — Madagascar’s violent illicit cannabis industry

Tons of cannabis are grown every year in the remote northern highlands of Madagascar’s Analabe region. However, even as legalisation is fast becoming a reality elsewhere in east and southern Africa, it remains strictly illegal in Madagascar. The cannabis-producing regions are home to armed trafficking groups, and cannabis production is a major cause of deforestation in Madagascar’s biodiverse northern forests.

This is Part Two of a four-part series — Part Three and Part Four will examine case studies from Mauritius and Seychelles. Read Part One here.

The rural commune of central Antsahabe in northern Madagascar is a fertile region for agriculture: cash crops such as cocoa, coffee, and the vanilla for which Madagascar is famous are all produced here. Yet there is another crop that is a major source of income for communities in the region: cannabis.

Despite Madagascar being a large-scale producer of cannabis, with high levels of domestic consumption, cultivation, sale and consumption of cannabis are strictly illegal in Madagascar. The situation remains even as legalisation for medicinal and recreational use is fast becoming a reality elsewhere in east and southern Africa.

“At the economic level, cannabis could be a very profitable source of revenue for local authorities,” said Mr Armel, the mayor of Antsahabe. “The risk lies in management at the level of public health and local consumption.” Currently, Armel’s administration draws no benefit from the cannabis market, which in the Antsahabe commune alone is estimated to produce at least 200 tons per year.

The mountainous region Analabe, part of the Ambanja district where Antsahabe is located, is one of the primary regions of cannabis cultivation in Madagascar. Yet Armel’s wish that cultivation could be transformed into a profitable and regulated legal market faces challenges: political resistance to cannabis legalisation, the environmental impact of cannabis production and insecurity in remote cannabis-producing areas.

Regional trends towards decriminalisation

In 2017, Lesotho became the first country in Africa to issue licenses for the production of medicinal cannabis, which has quickly led to large-scale international investment to develop the sector in the landlocked mountain kingdom. In April 2021, one Lesotho-based cannabis producer received the first approval for an African company to sell medicinal cannabis in the EU.

Other countries in eastern and southern Africa have since followed suit. In October 2020, Rwanda became the latest country in the region to approve medical cannabis production for export, following in the footsteps of Uganda, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Zambia.

South Africa, which in 2018 became the first country in the region to legalise cannabis production and consumption for recreational use (but not commercial sale) through a ruling by its Constitutional Court, recently released a draft national master plan for the development of the commercial cannabis market, for both local consumption and export.

In Seychelles, cannabis use for medicinal purposes (but not cultivation as a crop) was approved by law in July 2020. The development was welcomed by some activists in the island nation as a step towards liberalising the law and the potential future approval of cannabis for recreational use. In the lead-up to presidential elections in late 2020, Alain St Ange, leader of the One Seychelles party and former minister of tourism, argued that Seychelles could benefit from “cannabis tourism” by legalising it for recreational use, which sparked debate in local media. Likewise, there is a significant lobby for legalisation in Mauritius, although cultivation and use remain criminalised.

These developments have led to optimistic analysis that the crop could be a new “green gold” for Africa. A report by the cannabis industry research group Prohibition Partners estimated that by 2023 the cannabis market across the whole of Africa could be worth approximately $7.1-billion. Another analysis, from strategy consultancy Birguid, estimated that the cannabis market in southern Africa alone generated just over $1-billion in revenue in 2019, primarily from the illegal recreational market.

In several ways, the cannabis market in Lesotho parallels that of Madagascar. The mountainous ranges of both countries provide environments well suited to growing cannabis. In both countries, cannabis was grown traditionally for many years before being criminalised under colonial rule, and cultivation then continued as an illicit market supplementing the incomes of subsistence-farming communities. Politically, however, it seems that Madagascar is showing no sign of following Lesotho’s lead.

In the countries that have embraced the development of cannabis markets, whether for medicinal, industrial (such as for hemp production) or recreational purposes, the policy shift is widely expected to bring economic benefit. Yet regulating the sector has its challenges. In Lesotho, for example, small-scale local growers have faced steep fees for cannabis-production licences, which some say sways the market in favour of multinational companies and forces smaller growers onto the black market. Allegations have also emerged of corruption in the allocation of licences.

In Zambia, Peter Sinkamba, president of the opposition Green Party, summed up how the benefits of cannabis production may also bring risks: “Depending on how properly this is done, this could just change the face of Zambia’s economy,” he said in an interview with Reuters. “This could be a blessing or a curse, like diamonds and gold, depending on the policy direction.”

Cannabis production in Madagascar

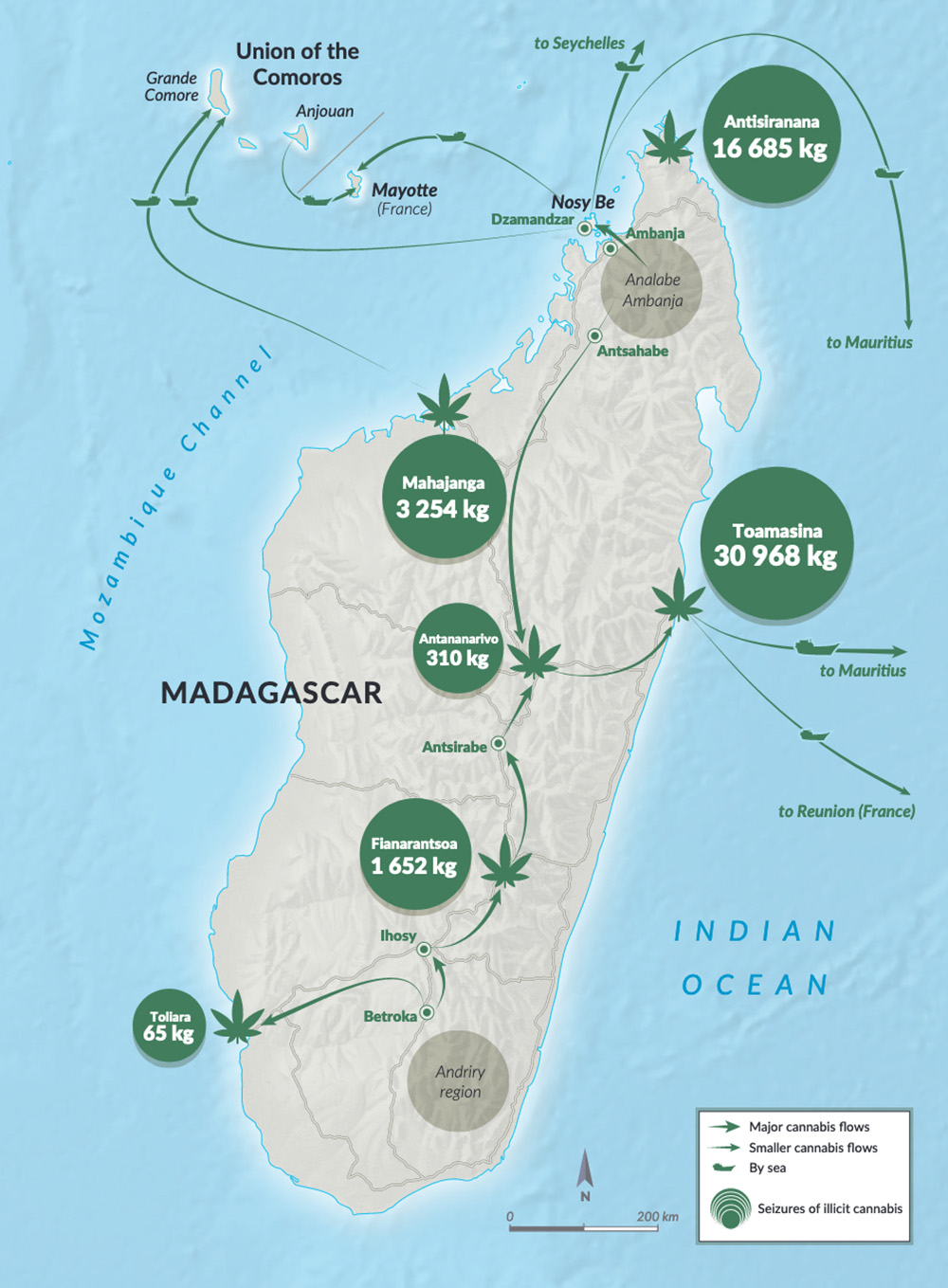

Madagascar is the most significant producer of cannabis among the western Indian Ocean islands. The major regions of production — Betroka in the south and Analabe in the north — largely supply domestic markets, particularly Madagascar’s urban centres, including the capital, Antananarivo. Some cannabis is also smuggled to other island states, including Seychelles, Mauritius, the Comoros and Mayotte. Our research has found that at around $0.03 per gram (in 2020), cannabis prices in Madagascar are far lower than in the other island states (as shown in the figure below), reflecting a plentiful domestic supply.

Consumption and sale of cannabis in Madagascar are widespread. Reliable estimates of consumption are not widely available, but figures do suggest high levels of recreational use. The latest statistics reported by the Malagasy government to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime’s annual data-gathering exercise indicate a 9.1% prevalence of cannabis use among the adult population, which would place Madagascar among the highest rates in Africa. This figure, however, dates from 2004.

Cannabis research consultancy New Frontier Data reported in 2019 that 14.2% of the adult population of Madagascar had reported using cannabis in the past year, which would equate to over two million people and place Madagascar as having the ninth highest rate of use in Africa.

Estimates for the amount of cannabis produced in Madagascar are also elusive, yet reports from law enforcement operations give a sense of its scale. Madagascar’s Gendarmerie Nationale seized close to 53 tons of cannabis in 2020, which included multiple seizures of more than one ton. In May and June 2020, an operation by the gendarmerie unit of Antsiranana, which oversees the region of Analabe Ambanja, seized more than 16 tons of cannabis and 21 litres of cannabis oil, destroyed over 80,000 individual cannabis plants, and led to the arrest of 80 people.

“Millions, even billions, of ariary (Madagascar’s unit of currency — 1 ariary [AR] = $0.00027) of profit are circulating in the sector, especially in the production zones of Analabe in the Ambanja district and that of the district of Betroka. Likewise, for the consumption zones like Antananarivo, cannabis brings in profit for big bosses and dealers,” said Tantely Ramamonjisoa, commissioner of the anti-narcotics division of the national police. ‘Big sums of money are at stake, which leads to the difficulty of eradicating this danger from society,” he concluded.

Analabe Ambanja: A centre for cannabis production

According to Armel, the Analabe region attracts trafficking networks from across the country. “There are traffickers coming from Mahajanga, Antananarivo and other provinces of Madagascar,” he said. Testimony from residents of Antsahabe and the surrounding area confirmed that hundreds of traffickers operate clandestinely in the area.

Although some residents collaborate with law enforcement officials, serving as informers or guides in remote areas, a significant proportion of the population cooperates with trafficking networks. Local young people work with cannabis producers in cannabis fields or participate in transporting cannabis to and from collection points, using their knowledge of the local terrain. Cannabis production is a source of revenue for many residents in the region.

Cannabis is transported on foot, with journeys continuing for two days or more. Produce is taken from the fields to either trucks (for transport to urban markets) or warehouses in neighbouring cities such as Ambilobe. “For the transit from Analabe to Ambanja town, there are several options. Either overland, by car or on foot, or transferred by river. Finally, there is the sea route for exports destined to the Comoros, Mayotte and other Indian Ocean islands. These journeys earn money, and there are enormous sums invested,” said Armel. The gendarmerie unit in Ambanja also reported that there are artisanal factories that produce cannabis oil in the region, yet these locations have not been identified by police.

Those in charge of trafficking networks invest large sums to purchase cannabis, transport it and secure safe delivery. According to members of the local community in Analabe, local farmers may sell a kilogramme of green cannabis at AR20,000 ($5.34). This is reportedly comparable to prices for cocoa, which depending on the season will sell for around AR25,000 ($6.67). Traffickers’ expenses for ensuring safe transport of the product to warehouses (for example, in Antananarivo) can amount to more than that sum per kilogramme. “But this amount varies, according to the trafficker involved,” explained Tombo Simon*, a young dealer based in Ambanja. “In our experience, from time to time and especially when we have more orders than usual, the transporters and farmers raise their prices. They also play on the rule of supply and demand,” he added. When finally sold to consumers, a kilogramme of cannabis can earn a trafficker between AR100,000 and AR150,000 ($27 — $40).

‘They shoot without warning’

Local government figures such as Armel and members of the community expressed their support for creating a legalised cannabis market as a way of regularising the profits and livelihoods that the trade brings to the local area. However, creating a controlled and regulated market would face serious challenges. Slash-and-burn agriculture, as used in cannabis production, has been identified as a leading cause of deforestation in Madagascar’s northern reserves. These forests are home to many endangered species, several of which are unique to Madagascar.

Communities also report that cannabis trafficking groups in Analabe are heavily armed and impose their own rule of law in production areas. Lieutenant Tahiana Antrefinomenjanahary, coordination officer at the Gendarmerie Nationale in Ambanja, said “law enforcement do not dare venture into this region [Analabe]. These are truly cartels who don’t hesitate to kill.” This was confirmed during focus group discussions with local members of central Antsahabe. Our research has previously identified similar dynamics in Betroka, in the south of Madagascar.

Colonel Mamy Marly Ramaromisamalala, head of the counter-narcotics unit in the high command of the Gendarmerie Nationale, gave more details. “In the case of Analabe Ambanja, even the gendarmes cannot venture into the forests, because the traffickers have Kalashnikovs. They shoot without warning… all military interventions in these regions demand specific precautions. We are very careful, because the traffickers benefit from their mastery of the terrain and support of the surrounding inhabitants.”

Lieutenant Tahiana Antrefinomenjanahary regards the cannabis market as a major factor in criminality and insecurity in the Analabe region. In his view, and also that of other law enforcement bodies in the region, the fight against organised cannabis-trafficking groups is one of their key priorities. In contrast, other drugs markets in Madagascar, such as for heroin and cocaine, are not associated with high levels of violence. Our previous research found that at a national level, countering drugs markets has not been as high a priority for law enforcement as, for example, illegal trade in natural resources and wildlife.

Police resources in Madagascar are limited, which has rendered it difficult for police to control a vast and criminalised cannabis market effectively. In Madagascar’s cities there is, on average, only one officer of the national police for every 3,000 inhabitants; in rural areas, where the Gendarmerie Nationale has jurisdiction, there is one gendarme for every 4,000 residents.

According to Raherimaminirainy Zoly Miandrisoa, former commander of the Gendarmerie Nationale brigade at Djamanjary on the island of Nosy Be, law enforcement in Madagascar does not have sufficient means to pursue cases of international export of cannabis. “For the moment, we are content with local arrests of consumers and dealers,” he reported.

One widely used argument in favour of creating legal cannabis markets is that it could free up overstretched police resources to be used in countering more serious and violent crimes. Yet in Analabe, creating an effectively regulated market would mean confronting groups involved in the cannabis market who present a violent challenge to the rule of law.

Not a political possibility in the near future

The legalisation of cannabis in Madagascar, for any purpose, does not seem to be a major political possibility in the near future, in contrast to the situation in other countries in the region. The optimism of the population of Analabe and local political leaders has not yet resulted in a political shift at the national level. If Madagascar were to follow the example of other eastern and southern African countries, any new policy would face a complex balance between the potential economic benefit to rural communities, governance issues endemic in cannabis-producing regions, and concerns about the effect on biodiversity and the unique ecosystems of Madagascar. DM

*Not his real name.

This article appears in the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime’s monthly East and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin. The Global Initiative is a network of more than 500 experts on organised crime drawn from law enforcement, academia, conservation, technology, media, the private sector and development agencies. It publishes research and analysis on emerging criminal threats and works to develop innovative strategies to counter organised crime globally. To receive monthly Risk Bulletin updates, please sign up here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.